Emacs is the 2D Command-line Interface

One of the most popular arguments against Emacs is that it is “a great operating system, lacking only a decent editor”. The promotion of the idea of “Living in Emacs” by some of the hardcore Emacs users only make this argument more compelling. At the first glance, using a single program for “everything” does seem to contradict the Unix philosophy, which favors single-purposed programs that compose really well instead of monolithic systems that try to solve many complex problems at the same time. In this article, I’d like to argue that Emacs largely follows the Unix philosophy in its problem domain: working with text, and can be seen as a two dimentional version of the command-line interface (CLI).

This is the Unix philosophy: Write programs that do one thing and do it well. Write programs to work together. Write programs to handle text streams, because that is a universal interface.

McIlroy, head of the Bell Labs Computing Sciences Research Center

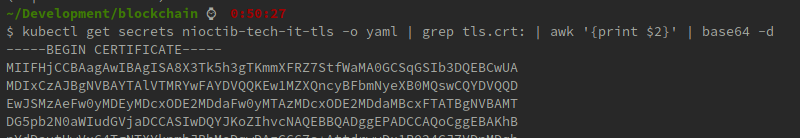

Many CLI tools stood the test of time. Programs like find, grep, awk, etc have been indispensable for IT professionals for decades. They are effective, sometimes more so than their GUI counterparts, because command line interpreters such as Bash provides an environment where they can be composed together to accomplish tasks that the original designer of the individual program have never thought about. For example, through the composition of kubectl, grep, awk and base64, the following command displays the content of the tls.crt certificate in a Kubernetes secret called nioctib-tech-it-tls:

The following two things are quintessential to the composibility and extensibility of the CLI programs:

- Text streams as the univeral interface

- Command line interpreter as a programming environment

There are definitely disadvantages to use text streams as the universal interface between programs due to its lack of structure. But the timelessness of many of the programs following this pattern and the prosperity that it brings to the CLI ecosystem proved its effectiveness as a design choice. Text can be read by both human and programs. It can be manipulated, printed, stored, trasferred, version controlled with the tools of your choice. For programs that do not inheritantly require structured data, using text streams as interface provides the most flexibility and composibility.

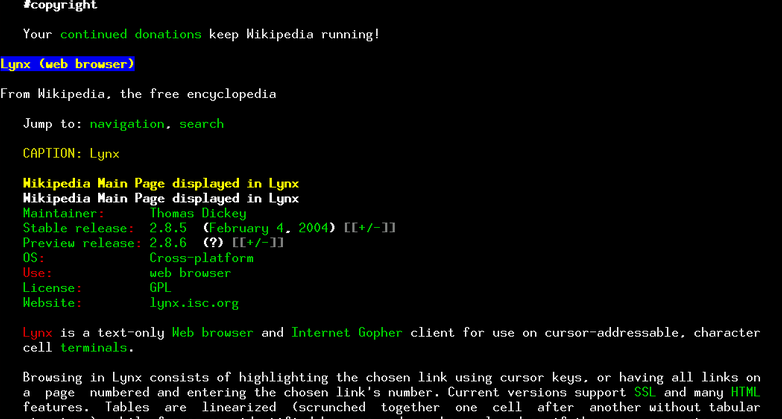

However, the flip side is that for programs that do require structured data, such as browsers, image viewers, music players, etc. Their text based versions usually become the toys of the hobbyists with neglectable impact.

Lynx: a text based browser with tiny user base

Lynx: a text based browser with tiny user base

Another important contributor to the success of many of the CLI programs is the fact that they live in a programmable environment. In Bash, programs can be written from scratch or glued together using Bash script. This makes the CLI environment infinitely extensible. By enabling smaller programs that “do one thing and do it well” work together to accomplish more complex tasks, it becomes an environment that boosts synergy, productivity and creativity.

The word “line” in the CLI (Command-line interface) environment indicates its one dimentional nature. For programs that potentially need to interact with (two-dimentional) text files, Emacs offers an environment with similiar characteristics that makes CLI enviornment successful: A universal text interface and a programming environment which enables infinite extensibility.

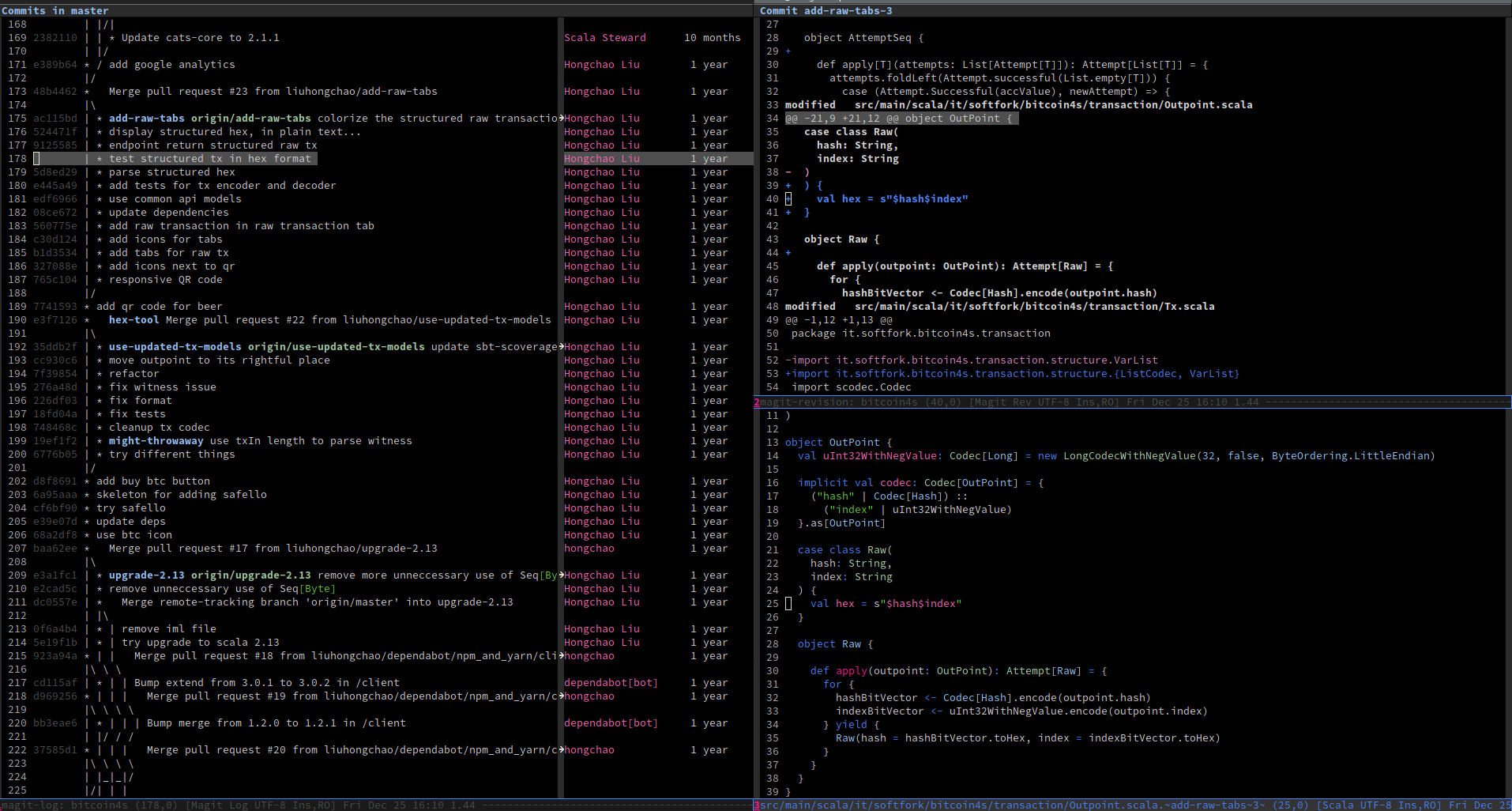

Self described as “an extensible, customizable, free/libre text editor”, GNU Emacs’s infinite extensibility is enabled by a Turing-complete language called Elisp, which also is used to write most of Emacs itself. This is similiar to how for example Bash achieves its extensibility through Bash script. Just like most of the programs that thrives under the Bash environment are inheritantly text focused, most of the popular Emacs programs are text focused as well, such as Magit and Org-mode. They also tend to integrate very well with other Emacs programs, creating synergy similiar to that of the CLI programs. For example, you can look at the commit history of a Git repository using Magit, jump directly to the diff of a commit, and then jump straight to the source code in the diff. In the following example, the source code is written in Scala, you can then edit the code with Emacs’s exellent Scala support thanks to lsp-mode and lsp-metals, which are programs in the Emacs ecosystem that Magit is not aware of at all.

Magit: jumping from commit to diff to source code

Magit: jumping from commit to diff to source code

If Emacs is an environment for programs that focus on two dimensional text, it is also more than capable of running programs that deal with one dimensional text. In fact, many CLI tools such as grep, find and many file system management utilities (Dired) are implemented in Elisp and thus integrated into the Emacs ecosystem as well. This is one of the reasons that if your main workflow is text focused, “Living in Emacs” is probably not a terrible idea due to the synergy many of these Emacs programs produce.

However, that doesn’t mean that everything should be run in Emacs. Emacs is probably not the best tool for browsing web (EWW) or listening to music (EMMS), just like CLI tools such as Lynx will never have significant impact because they are fundamentally not text focused. The argument that Emacs is “a great operating system, lacking only a decent editor” tries to paint Emacs as a monolithic swiss army knife ambitious enough to run any programs. In fact, Emacs is more like a two dimensional CLI environment that embraces the same Unix philosophy: enable simple, elegant programs interacting with each other using an univeral interface.

Edit: